Bioware's Mass Effect or a deep dive into travesty

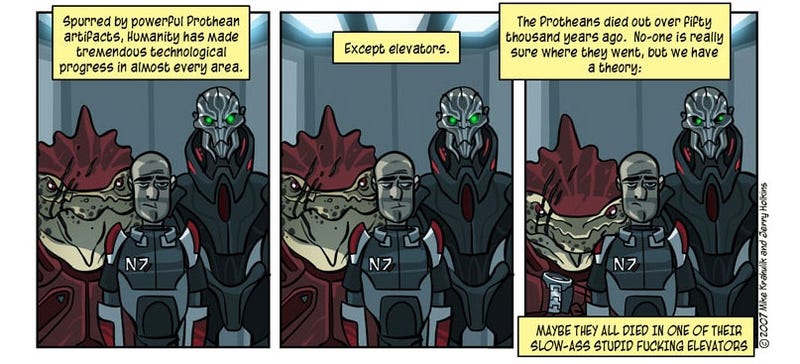

Alright, let's take a delightful stroll down memory lane with the OG Mass Effect. Picture this: elevator rides, more elevator rides (just like Babylon 5, but less dramatic music), endless sprints like you're training for the galaxy's longest marathon (because that's how classic CRPGs roll), and open locations galore – planets where you could stumble upon giant worms, because what's a space adventure without a giant worm or two? Thresher maw, you magnificent cosmic noodle, we're looking at you.

The game had more side quests than a space bar has different alien species. Mining minerals for the Earth Alliance? Shepard was practically a cosmic geologist with a side hustle in intergalactic Uber. And let's not forget those side quests – not as thrilling as the main game, but hey, in this well-crafted universe, we can forgive a few quirks. It's like dating; you love the main story, but sometimes you're stuck with a side quest that's about as interesting as watching space paint dry. Mass Effect had more ways to complete quests than Shepard had love interests. Many ways were hidden, like Easter eggs in a galaxy-sized basket. You'd discover them, and suddenly you're the Commander of Easter, handing out space eggs and leveling up your charisma stat.

And speaking of love interests, Shepard was a bit of a heartbreaker. Sure, you could save the galaxy, but managing relationships? That's a questline more complex than navigating a black hole blindfolded. It's like, "Hey, I saved your species, but can we talk about us?" Galactic savior, relationship counselor – Shepard truly did it all.

And let's not forget the all-important dialogue choices. Shepard had three options: neutral, aggressive, or courteous. It's like choosing responses in a cosmic version of "Choose Your Own Adventure," where the fate of the galaxy depends on whether Shepard decided to be a sass-master or a galactic teddy bear.

Mass Effect didn't just revolutionize the CRPG genre; it turned storytelling into a cinematic masterpiece. During dialogues, characters moved, gestured, and got so emotionally invested that you half-expected them to pull out space popcorn and start a watch party. "Shepard, darling, grab a seat, the drama's about to unfold." The grand battle for the Citadel was so epic that even the Reapers were taking notes for their next invasion. "Dear Diary, today we faced Shepard and crew, and they put on a show better than a supernova. Note to self: improve space battle tactics." But here's the kicker – how do you fight an army of Reapers? It's like trying to take on a buffet with a toothpick. You might nibble at one Reaper, but there's a whole intergalactic feast waiting to devour you. Shepard was basically the galaxy's food critic, giving Reapers a one-star review: "Too many limbs, not enough personality." So, what did we learn from Mass Effect? Elevators can be a mood-killer, love is as complicated as navigating a cosmic obstacle course, and fighting Reapers is like trying to fold a fitted sheet – frustrating, and you're not entirely sure if you're doing it right.

Mass Effect, you glorious space soap opera, you've left an indelible mark on our hearts, reminding us that in the vastness of space, there's always room for a good story, a few laughs, and the occasional giant space worm. And that, dear space traveler, is the comedic saga of Mass Effect – where romance is as unpredictable as a comet's path, and Reapers are the unexpected party crashers of the galaxy. Until next time, space cowboy. Now let's talk about Mass Effect 2.

The saga unfolds in a world where the population wonders if it's worth croaking for the sake of drama. Enter Mass Effect 2, where the ambiance is hotter than a Krogan barbecue, and I found myself caught between two factions (not literally, thankfully). Yet, it seems all this happened just for the second act to be treated like yesterday's leftovers – a dish not worthy of our attention. Admittedly, the game's quality reached new heights, playing out like a more sophisticated soap opera than the first installment. However, the potential that was supposed to sprout from the initial game and blossom into something novel was squashed to cater to the masses, turning the once promising space odyssey into a guessing game for Call of Duty aficionados.

Let's reconstruct Shepard, following the Babylon 5 paradigm! In Mass Effect 2, he emerges as if concocted in a lab – a counterfeit, a surrogate. Project Lazarus, making sense in Babylon 5, is practically nonexistent in Mass Effect. It postured itself as the Babylon 5 of gaming—honest sci-fi with good storytelling and dramatic music designed to blindfold us from the truth. Babylon 5's Project Lazarus brought back war veterans as cyborgs controlled by Psi-Corps. Mass Effect attempts a similar feat, minus Shepard's heroic death; he simply burns up in a planet's atmosphere. That's it – he's toast. Yet, Project Lazarus sees potential in the smouldering remains, severing the scientific tie established in the first part. Post-reconstruction, Shepard struts around as if death was a mere inconvenience. There are dialogues that raise eyebrows, but the essence is a casual 'I died, big deal.' The crew doesn't seem bothered by the fact that they are supposedly in the presence of the real Shepard, with no conflicts or debates to address this.

Project Lazarus, making sense in Babylon 5, is conspicuously absent in Mass Effect. The trilogy ambition from the first part is lost in the second, akin to a spin-off without clear direction. Witness Shepard, resurrected, casually strolling on the Normandy – a testament to the weird amalgamation of Mass Effect and Hollywood.

A humorous observation stems from the crew stranded on a planet for ten years, clinging to the weapons they had at the time. Logically, we should have those same weapons now, but the whole scenario is a joke – not something to be taken seriously, even in Mass Effect's universe. It's a comical farce, proving that armoury distribution is just as unreliable as a Krogan's digestive system. Picture this cosmic conundrum: Mass Effect's universe, where one moment you're zapping enemies with energy weapons in the first instalment, and the next, you're handed a bag of ammo in the sequel. It's a logical leap that rivals a quantum teleportation mishap.

In the initial space opera, guns went pew-pew without the need for pesky ammo. Fast forward two years (or two in-game minutes, considering Shepard's fiery escapade), and suddenly, the entire galaxy has switched to conventional weaponry. It's like Mass Effect's version of an interstellar Black Friday sale – everyone must have fresh bullets, and we'll ignore the absurdity of acquiring ancient weapons ten years into the future. The transition from energy-based elegance to ammo-hoarding absurdity is comically highlighted in Jacob's side quest. Picture this: after a decade of dragging out a mundane existence on a planet, they somehow manage to drag in only the new weapons. It's as if the entire galaxy collectively decided, "Let's conveniently switch armament just to keep things interesting." So, here we are, attempting to make sense of a universe where ammo is now the precious currency, and the once-advanced technology decided to do a retrograde moonwalk. It's a humorous nod to the gaming gods, a deliberate twist that BioWare pulls off with a sly grin – acknowledging the inconsistency while embracing the chaotic dance between cosmic logic and pure, unadulterated absurdity. In the end, Mass Effect 2 seems more like a cosmic comedy than a serious sci-fi game. Perhaps BioWare never intended to leave a cliffhanger or provide insights into the series' future but opted to toss us into another dimension. For now, it's undeniably another bizarre journey in the Mass Effect universe, echoing the whimsical humor of Arthur C. Clarke while dancing on the fine line of cosmic gibberish. Behold the cosmic comedy of Mass Effect's sequel – a space soap opera where logic takes an interstellar vacation. The intricate dance between Shepard and Cerberus unfolds like a poorly written script in a parallel universe. In the first act, a crucial opportunity was missed to explore Cerberus as potential future allies or, dare I say, the new hires at Shepard Incorporated. A simple nod in the initial chapter could have seamlessly woven Cerberus into the narrative fabric, establishing a harmonious connection instead of the abrupt "surprise, we're working together now" plot twist.

The RPG essence, once a sturdy pillar in Mass Effect's architecture, falters like a clumsy dancer in Shepard's awkward conversations. Dialogues meander through inconsequential chit-chat, rendering role-playing mere pantomime. Shepard, the supposed master negotiator, either vehemently rejects or begrudgingly accepts alliances, resembling a child pouting about sharing toys. Then we dive into the tangled web of Shepard's former crew, now toiling away for Cerberus. It's a drama rivaling the best soap operas – Shepard's allies mysteriously switching loyalties, revealing a reputation debacle that'd make interstellar headlines. It's like your trusted barista suddenly joining forces with the coffee beans against your caffeine cravings. Mass Effect 2 transforms into a galactic therapy session where Shepard, our fearless leader, must play cosmic counselor to resolve everyone's familial troubles, from fathers to sisters, sons to daughters – even distant relatives make a cameo. It's a sitcom-worthy spectacle where Shepard, the savior of the galaxy, moonlights as a cosmic therapist.

The transition from the first to the second act is as jarring as a teleportation mishap. While the inaugural installment laid the groundwork, introducing Saren, exposing Reaper threats, and concluding with a logical crescendo, the sequel veers into a side quest – a collector's edition, if you will. The parallels to Babylon 5 become glaring; Mass Effect seemingly pays homage, but the execution is akin to a cosmic farce. The ominous reapers now relegated to plot devices, controlling collectors who resemble creepy creatures from a bargain-bin horror game. The once-grandiose tale of saving the galaxy is reduced to a space-faring recruitment drive, reminiscent of a bleak Silent Hill spin-off. Shepard gathers a motley crew for a suicidal mission, a plotline seemingly concocted after a night of cosmic cocktails. The galaxy-saving saga takes an absurd turn, leaving us questioning if this is the masterpiece we anticipated or an elaborate joke.

As the plot unravels, the very fabric of Mass Effect's once-epic narrative seems to fray. It's a tragicomedy where our expectations collide with the unscripted chaos of BioWare's cosmic playground. The sequel transforms into a playground for absurdities, a space-themed sitcom where characters' logic takes a nosedive, and our hero is reduced to playing interstellar family therapist. And so, the cosmic drama unfolds, leaving us both bewildered and amused in this twisted galaxy far, far away.

As anticipated (though I was hopeful that Bioware would redeem itself in the third part), the sequel continued the trends of the second, forsaking its role-playing roots for a more shooter-oriented venture. Alas, Bioware promised a grand RPG spectacle, but what we got was an abundance of gun upgrades for the multiplayer mode, a choice between two different evolved species of aliens, and armor upgrades. In essence, it transformed into a playground for the younger generation, contrary to the mature tone it was known for, perhaps aimed at the children approaching adolescence.

In Mass Effect 3, watching cutscenes with Shepard feels like watching a television show, a departure from the immersive experience one would expect from an RPG. The scenes, however, are lavishly produced, turning the game into a mere spectacle, drenched in realism and logic (or the lack thereof). In the attempt to protect Shepard, the Reapers, with him standing in plain sight, seem to shoot everything else but him. A shuttle filled with civilian children becomes more crucial to the Reapers than Shepard's ship, providing a stark commentary on the priorities of intergalactic villains. Speaking of children, who, by the way, annoy us, Shepard faced some severe trials in the first game when he had to make the hard choice of sacrificing his unit. However, this trauma seems to have been conveniently forgotten in Mass Effect 3. The disappointment I observed can be linked to the fact that the writer from the first game departed after its completion. Once I discovered this, the tangled narrative of Mass Effect 2 and 3 began to make sense, forming a labyrinth of confusion. In the first game, Cerberus was portrayed as a simplistic organization merely trying to acquire technology. However, by the third installment, Cerberus has transformed into a formidable army rivaling the entire fleet of the Alliance, precisely when Earth finds itself in dire straits. About two-thirds of Mass Effect 3 involve battling fellow humans — a travesty! This also aligns with Mass Effect 2, where Shepard is never given the option to join Cerberus or not. Even the capture of the political center and Citadel is done by humans themselves. The Reapers seemingly understood the importance of capturing this point, as evident in Mass Effect 1, to secure control of the relay. Still, in Mass Effect 3, they leave it unattended, providing an open invitation for enemy forces to gather for the final battle.

In conclusion, the extinguishing of the relay in Mass Effect 3 paradoxically allows for a victory over the Protheans, even though they could have achieved the same result without extinguishing it. The relay was a crucial element in the first Mass Effect, emphasizing the importance of control for the Reapers. Unfortunately, much like the diminished significance of the Spectres from the first game, Mass Effect 3 diminishes several vital elements and plotlines into oblivion. Mass Effect 1 placed significant emphasis on the revered Spectres, a focus that faded into obscurity in the subsequent series, leaving much to be desired.

The second part, in its eagerness to appeal to younger audiences, sacrificed many critical elements. In the third part, this degradation reaches new heights. The presence of Cortez, sobbing about losing his husband and appearing in tears every time you interact with him, seems excessive. It almost appears as if he lost his husband just before every conversation. Poor chap! Perhaps, if the end had been a poignant comedy, we might have remembered something positive about this game. Alas, it was not to be, and Mass Effect remains etched in memory as a degradation not just of the series but of Bioware as a whole (especially after the disappointing Dragon Age 2). Such is the way of things. In the cosmos of Mass Effect, there were myriad storylines from which a splendid melange could have been crafted. Take, for instance, the enigmatic Keepers from the first part—forgive my fogginess, but their significance seemed to vanish like dew before the sun. I ponder if they were the clandestine architects of the Reaper's triumph. Notably, the Reaper dispatched in a mission-gone-awry during Mass Effect 2—its demise, a silence echoing louder than the mission itself.

As legend has it, before the game's internet debut, an anonymous soul spilled the details of Mass Effect 3, weaving a tapestry intertwined with dark energy, a concept frequently caressed in Mass Effect 2. The tale spun of ancient races converging to quell the menace of dark energy—a threat looming over the entire galaxy. The construction of the Human-Reaper, borne from the genetic diversity of mankind, was purportedly a desperate attempt to aid this cosmic confluence. In the end, Shepard could have concurred to sacrifice humanity for the biomass needed to forge the Reapers, evoking a cosmic apocalypse akin to Reynolds' grand cosmic tales—perhaps that's why this version faced the editor's blade, yet a gem it remains.

Now, let us unveil the spectacle that was, the peculiar spectacle. Shepard's coalition waged war against the Reapers for Earth, equipped with a formidable armada. Alas, the key to this celestial arsenal lay dormant on the Citadel, brought to Earth by the Reapers and securely locked. With the possibility of entering through the portal in London, Shepard makes a dash but is abruptly intercepted by a Reaper. A projectile whizzes past Shepard, and the screen fades to white—therein begins the perplexities.

Shepard awakens, ambles to the portal, discharging a peculiar pistol of unknown origin into the abyss. He finds himself in a realm unfamiliar, not akin to the Citadel. A spectral dialogue unfolds between a phantom harbinger, claiming control over the Reapers, and Anderson, advocating perseverance. Shepard, amidst his turmoil, succumbs to an ethereal force, slaying the phantom. Shepard then confronts a larger-than-life apparition, revealing himself as the Catalyst—a crucial entity required by the Reapers. It divulges that it has created the Reapers because organic life always ushers synthetic life, and this cycle inevitably results in the extermination of organics by synthetics.

The Catalyst, our divine narrator, presents three options: assimilate with synthetic life (Shepard and the Reapers), control the Reapers (which inexplicably requires self-sacrifice), or synthesize organic and synthetic life. After all the cosmic banter, Shepard chooses self-sacrifice, standing before the energy conduit, illustrating how the Normandy, in a futile escape attempt, miraculously evades the explosion but crashes on an unknown planet. Characters emerge from the wreckage, realizing that this narrative was an account of Shepard, narrated by an old man to his grandson, Boris Moiseev. The last words on the screen, downloadable content awaits, and I, in a fit of rage, transform into Torque and terrorize Botanica for a year.

Before delving into this novelist play by BioWare and Electronic Arts, let's recall what they promised and delivered in Mass Effect 3:

- They promised that the Rachni would have a significant impact on the plot – well, at least in the final battle with the Reapers.

- They boldly declared the game would have numerous endings, adding, "After traversing three games with your smooth-talking Shepard, we'll bring you a finale so dazzlingly convoluted that it puts everything to shame." They contradicted themselves, didn't they, these creatures?

- Someone suggested that the essence of Mass Effect 3 was to answer all the questions the series had created when it made a pact with the sequel.

- Another quack claimed that "the narrative line concludes with the third part, meaning the endings can be very different, not like the typical A, B, or C choices in other nonsense. In the end, the conclusions may make a lot of sense and depth." This last phrase has such a degree of audacity that it matches the grandiosity of a well-dressed animal.

- Another being said that playing in multiplayer was not mandatory, but oh, how we collected resources along the way. All resources are divided into two – if the indicators are less than 2800 AP, you don't get the green option (which doesn't make sense anyway, and has nothing to do with the synthetic-organic synthesis). But if you have more than 4000 AP, you can choose the red option. Then, a short scene is shown with the ruins of Earth and Shepard's armor and sigh – all Shepard. Achieving 4000 is impossible without playing multiplayer; this was promised, even though it was made worse than Call of Duty. Now, they even dare to claim that they justified the ending of the third part, hiding what we did all this time throughout the Mass Effect history, a super-paragon who saved the council, gave life to the Rachni, saved his crew, healed the Krogans, and brought peace to the Geth and Quarians.

- Finally, we come to Arrival in Mass Effect 2, where it is said quite directly that if the relay explodes, it will destroy the entire star system. But if we destroy all the relays, we save the entire galaxy. Even if we consider that not all life dies without relays, we cannot have normal life at great distances in other star systems. And even if we take into account that all these allegations are not true, we still wonder where the Normandy flew after the explosion, and what happened to the allied fleet.

Even if all my grievances are not correct, it still makes you wonder about the fate of the Normandy and the allied fleet. And this is just one of the many questions that have been left hanging since the second part, as could be expected. After the original scriptwriters left, the remaining people decided to create a deliberately open ending that explains as little as possible so that we can think about our own questions. This is what they said in "The Final Hours." The problem is that leaving things like the space jockey in Alien as an enigma is nice, as it maintains the aura of mystery when it comes to mystical realms. It's fine when such questions linger. However, it's not cool when we are left with everyday questions, like those presented in Mass Effect 3, which they never promised to do, and which is just a ploy to keep people running in circles while claiming that they're witnessing something divine. It's ridiculous how they constantly tout their work, never actually showing whether it is truly divine or if they are just deceiving us at every turn.

In my peculiar world, I am a devoted Silent Hill fan, and head-scratching is practically my middle name. I attempted to weave a connection with a toilet paper and make sense of the cryptic ending. However, it's safe to say that nothing was predetermined from the start. My main gripe with the ending is the sheer audacity of BioWare, thinking they could pull off something similar to Silent Hill at the end. Yet, they've never managed to get it right throughout the second and third parts. It's like they threw in a boss and called it a day – that's the extent of their prowess.

Let me try to clarify things from a psychological perspective. After Shepard gets hit by the laser, his subconscious begins to play out, like indoctrination thesis as seen with Saren. If we consider Anderson as a symbol of Shepard's consciousness, reminding him of his fight, the Reaper's manifestation convinces him that there is no option to control them (hence why they try to control Shepard and force him to shoot the admiral, proving he cannot control them). The three options – unity with synthetics represented by Saren, synthetic control, and the proposal by the Illusion, both present themselves as traps that manipulate Shepard's reasoning. The only canonical option is resistance, where Shepard resists the Reaper's attempt to indoctrinate him, and that's why he appears afterward in the same place where he was after the laser. This makes more sense and is the interpretation I've become accustomed to, at least providing a somewhat conclusive ending, which I'll consider as the canon.

However, reaching such an ending with Shepard requires playing multiplayer to gather the required strength of 4000. Only then does the red option appear, but it still lacks meaning afterward (as I clarified above).

In conclusion, I've accustomed myself to a certain ending, and I'll stick to that.

So here you have it, I've laid out my thoughts. But to strengthen this theory I believe in, I recall Arrival for Mass Effect 2, where Shepard attacked the Reaper artifact. Bringing this into the context of Silent Hill, it occurred to me to explain where the Illusion boy came from. Almost no one saw him during the third part except Shepard, and the Illusion's visions, induced by the Reapers, closely resemble the scene with countless babies when Shepard goes to the light. So, to further elaborate on my theory, I'd say that bringing Silent Hill into the study allows for a rather cruel interpretation. However, the beloved endings and cliffhangers are far too light and bring you towards them, especially since they weren't planned, and I've made up most of this myself. This doesn't end, though – shout and come up with your own story. But as for the extended cut, I don't want to hear or see anything about it. I spent a long time reading the entire scenario in txt, extracting all the facts, and remembering everything from the game. I've replayed the first two parts many times, except the third, which I've only played once. Now, my head hurts. To hell with it. Flushed.

And so, dear viewers, as we navigate the vast galaxy of Mass Effect, we've encountered epic battles, mind-bending choices, and a plot twist more complex than a Krogan's family tree. BioWare, in their quest to master the art of surprise, threw us into a Silent Hill-inspired finale, leaving us pondering the meaning of life, the universe, and whether Garrus ever truly calibrates anything.

And as we bid farewell to the Mass Effect saga, let's indulge in a humorous epilogue about Shepard's romantic escapades. Ah, Shepard, the Casanova of the cosmos, dancing through the galaxy, leaving hearts aflutter like EDI's circuits. In the realm of romance, Shepard was more prolific than the Mass Effect codex. From passionate rendezvous with Liara to a tumultuous fling with Miranda, our Commander's heart was a crowded nightclub with a "strictly no Reapers allowed" policy. And who could forget the heartfelt moments with Garrus – the Turian with a voice smoother than a Mako ride on a bumpy planet? Their love story could rival any Shakespearean drama, complete with laser rifles and tactical cloak rendezvous. But alas, the love carousel didn't stop there. Thane's poetic serenades and Tali's adorable shyness added more layers to Shepard's romantic odyssey. It was like a soap opera in space, with more aliens than a cantina on the Citadel. Now, for the romantic involvements that could've been – imagine Shepard and Wrex, two warriors forging a love as robust as their combat skills. The galaxy might not be ready for such a power couple. In the end, whether Shepard found true love or just an interstellar fling, one thing is certain – the Normandy wasn't the only thing rocking during those long interstellar journeys.

And with that, our Mass Effect odyssey comes to a close. Remember, in the vastness of space, love, laughter, and a well-timed space joke can be the best companions. Until the next cosmic adventure, this is Commander Shepard signing off – because saving the galaxy is serious business, but a good laugh is timeless.

Comments

Post a Comment