Bygone science of the century

In the midst of the bygone century, humanity harnessed the atom and embarked on the conquest of the cosmos, envisioning a future bathed in the luminosity of progress. There was a prevailing belief that, as the century waned, interstellar voyages would manifest, lunar and Martian colonies would thrive, mastery over the weather would be attained, and the specters of age and ailment would be exorcised. The ethereal promise of antigravity and rocket backpacks lingered like echoes of a cosmic ballet.In the echoes of Arthur C. Clarke's prose, where the sentient supercomputer HAL beckoned from the realms of '2001: A Space Odyssey,' a collective conviction echoed through the corridors of time – every hearth would welcome its own automaton. Yet, dreams, akin to phantoms, remained elusive. The cosmic saga concluded with Apollo 11's lunar landing, and humanity found itself ensnared in the confines of low Earth orbit. The lunar soil, last touched by human footsteps in December 1972, bore witness to an unfulfilled odyssey. The fabled antigravity devices and celestial rocket backpacks remained elusive. Hunger, maladies, the relentless march of time, and the inevitability of mortality persisted. The trajectory of progress, once celestial and atomic, veered into the terrain of silicon minds and mobile whispers.

Modern smartphones — more potent computing entities than the one that accompanied Neil Armstrong to the Moon. Yet, we wield them not to embark on interstellar journeys but to summon pizza deliveries or to unveil snapshots of cute cats on social networks. Why has faith in science and progress wavered? Why, instead of constructing new, sophisticated, reusable rockets, have tech manufacturers shifted their focus to churning out smartphone models that differ from their predecessors only in price, memory, and camera resolution?

Serious undertakings, like space exploration, demand significant capital, patience, and a willingness to embrace risks. While governments possess substantial funds and patience, the stream of state funding can quickly run dry if governmental priorities undergo sudden shifts. NASA's lunar program, with a budget of 22 billion dollars, concluded after the triumph of the Apollo moon landing. The US government, having claimed victory in the lunar race, shelved further plans for lunar exploration and drastically curtailed the agency's funding. The cosmos became economically unattractive. The cost of launching valuable cargo into orbit plateaued at $19,000 per kilogram and lingered there for many years.

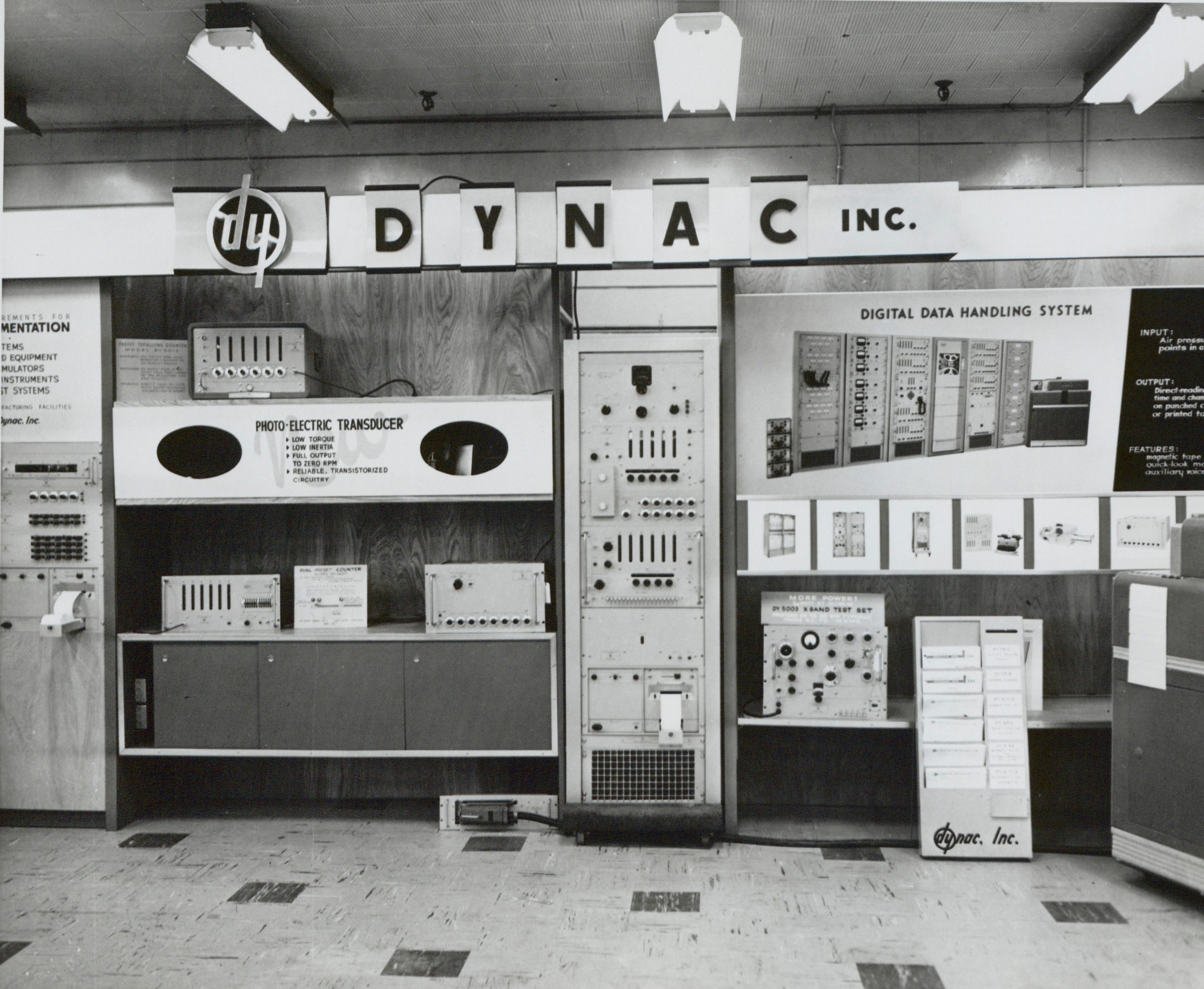

Success often favors the most insightful investors, those willing to believe and invest in the least obvious projects. The leadership of Hewlett-Packard once doubted the success of calculators, while IBM executives questioned the prospects of personal computers. Both decided to take a chance, and they did not err. In the 1970s, investors in Microsoft and Apple seemed like visionaries. In 1985, Steve Jobs was ousted from the company he founded, with leaders deeming his management methods dubious and potentially leading the company to ruin (only to later invite him back in 1997 when the company was facing challenging times).

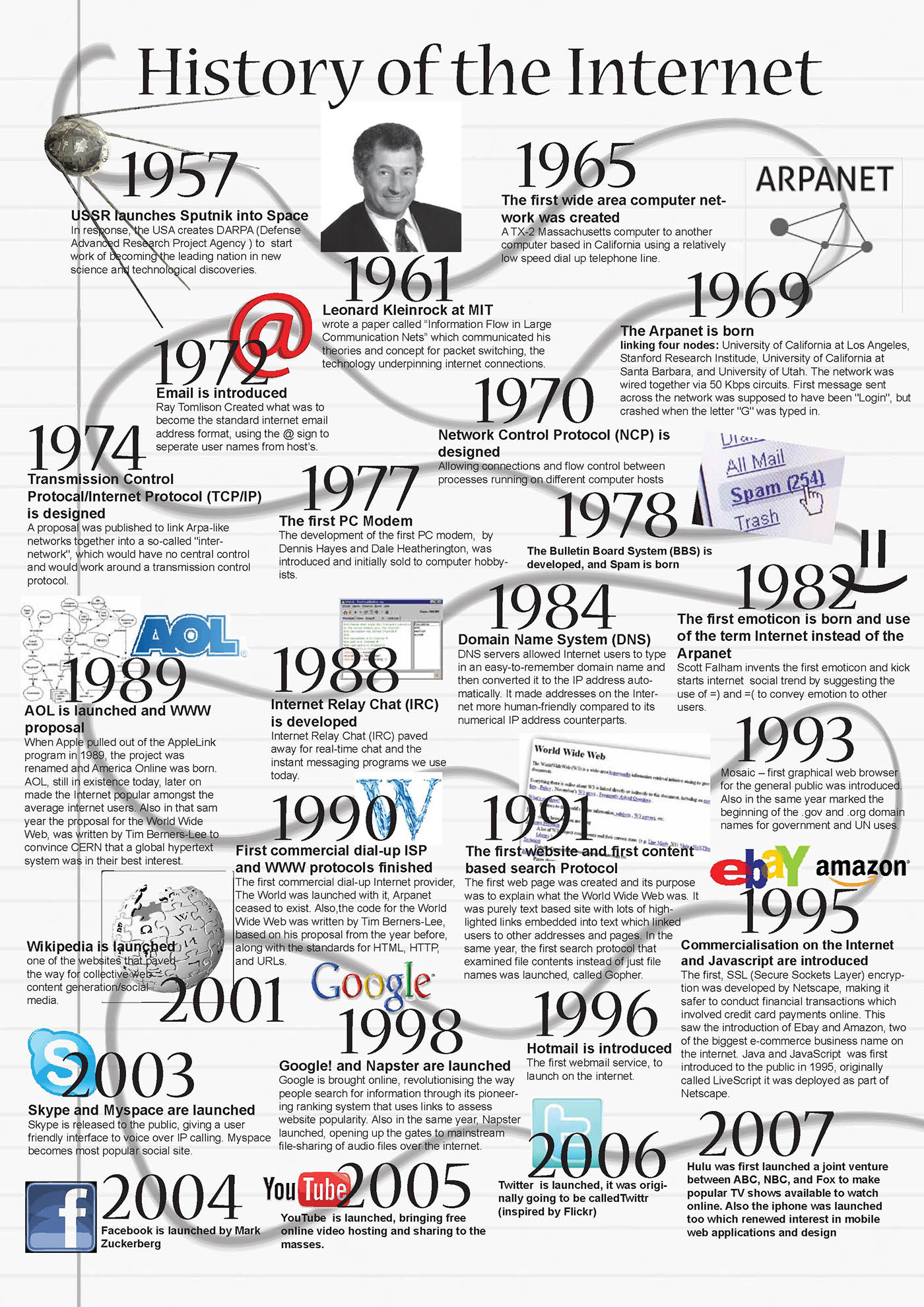

However, even those willing to take risks began to perceive rockets and nuclear energy as less promising sectors. In the 1970s, investments flowed into computer and information technologies; in the 1980s, into biotechnology and mobile communication; and in the 1990s, the internet took center stage. Investors grew increasingly reluctant to support fundamental projects requiring extended periods of implementation. Thus, space exploration continued to be funded primarily by governments — more out of habit than the anticipation of profit.

The shift towards information technologies and disillusionment with the future found reflection in mass culture. The 1980s saw the birth of the cyberpunk genre and a resurgence in the popularity of post-apocalyptic narratives. Cyberpunk emerged from the British 'New Wave' science fiction of the 1960s, serving as a counterweight to the utopian science fiction of the 1950s. Cyberpunk authors aimed for a more realistic portrayal of reality. While acknowledging the growing influence of digital technologies, they did not view them as an inevitable good. After all, society has a tendency to find perverse applications for any technology, no matter how beneficial.

Typical cyberpunk is a technological dystopia with a noir flavor. High technological development coexists with deep social stratification, poverty, and street anarchy. Governments have weak control, and real power lies in the hands of transnational corporations. The protagonist is often a lone hacker, a cybercriminal defending their freedom and principles against insatiable corporations.

The genre's heyday was short-lived; by the 1990s, the fantasies of Gibson and others began to feel outdated against the backdrop of real technologies. However, its influence on mass culture persisted. Even now, amid widespread nostalgia for the 1980s, we receive a dose of cyberpunk every year: 'Blade Runner 2049,' remakes of 'RoboCop,' 'Total Recall,' and 'Ghost in the Shell,' 'Mute,' 'Altered Carbon,' and more.

Gaining popularity in the late 1970s, post-apocalypse definitively buried the belief in a bright future. What kind of future can one talk about in a genre whose main idea is the demise of all civilization? Survivors of the apocalypse try to eke out a living, rejoicing in simple things like a can of dog food or a gasoline canister. That's the entire future.

In essence, apocalyptic plots have existed almost always. Myths about the end of the world are found in many cultures; the Bible concludes with the Revelation of John the Theologian, and the Edda with Ragnarök. The impending Judgment Day was eagerly anticipated in the Middle Ages. Mary Shelley's 1826 novel 'The Last Man' is considered one of the first representatives of scientific post-apocalypse. In the book, a large part of the Earth's population dies from an epidemic. Shelley's contemporaries did not appreciate the concept, and the novel was only reissued in 1965 when the theme of the last man on Earth suddenly became relevant.

After Shelley, the theme was touched upon by Herbert Wells and Jack London. The reasons for the catastrophe varied, but in most cases, humans were not to blame for the end of the world. This changed in the 1950s when the prospect of radioactive fallout suddenly became very real. 1950s sci-fi authors used the theme of nuclear apocalypse as a warning to their contemporaries. Their works reflected the fears of that time, giving us serious, complex, and socially sharp texts like Neville Shute's 'On the Beach' or Walter M. Miller's 'A Canticle for Leibowitz.'

In the 1970s and 1980s, post-apocalypse gained momentum again, but this time, entertaining action movies set the tone—'Damnation Alley' (1977), 'Mad Max' (1979), 'Warriors of the Wasteland' (1983), and the video game Wasteland. Images of lifeless deserts, lone wanderers clad head to toe in leather, and scantily clad damsels became the hallmark of the genre. With the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War, the threat of nuclear confrontation diminished, but confidence in a bright future did not increase. International terrorism, an ecological crisis, the thinning ozone layer—overall, in the late 1990s, post-apocalypse became fashionable again. Examples include the success of video games like Fallout and Half-Life.

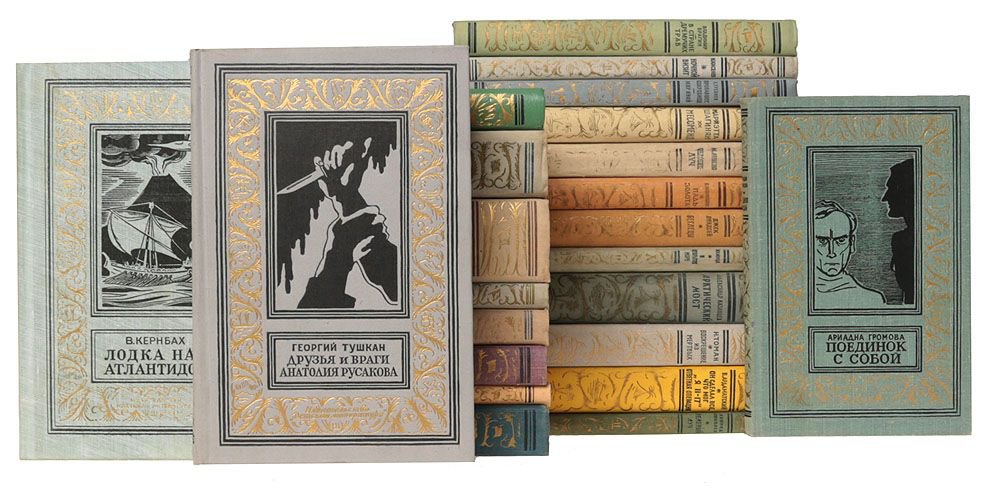

In the 2000s, the genre also found favor in Russia. Dmitry Glukhovsky's 'Metro 2033,' the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series, novels by Sergey Tarmashev, Dmitry Sillov, and Andrey Levitsky topped sales charts. Why? Fans of the post-apocalypse see in it the romance of wastelands, the opportunity to choose their own destiny, and a stark contrast to the familiar mundane reality. Few fans of the genre considered that in the case of a real apocalypse, their chances of survival are close to zero.

By 2017, the trend of post-apocalypse in Russia waned, but the disillusionment with the future did not disappear. It was time to take the next step—look back and decide that the past was much better!

There's nothing new in retro-mania—Renaissance artists admired ancient art. But in recent decades, this phenomenon has taken on industrial proportions. There's nothing surprising about it: the internet has simplified the path to retro content. If stumbling upon heartwarming relics used to require great luck, now a couple of clicks are enough to immerse oneself in another era for an entire evening.

First and foremost, retro evokes positive associations with people's childhood or youth. It serves as a kind of cultural code, allowing individuals to associate themselves with a bygone era and belong to a specific generation. However, many modern fans of the 1980s were born only in the mid-1990s, and that doesn't hinder their enjoyment.

The 1980s hold a special place in people's hearts. Cultural historians even joke that the trend for them has lasted longer than the 1980s themselves. The secret to this popularity lies in the richness and diversity of the culture of that decade. It wasn't limited to cyberpunk and post-apocalypse but encompassed numerous iconic music groups and genres, popular films, and TV series. It seems like the artists of that time were not limiting themselves in any way. Their imaginations took on bizarre forms, giving birth to 'The Dark Crystal,' 'Labyrinth,' 'Willow,' and 'Pee-wee's Playhouse.'

Journalist and avid gamer David Walt, in his book 'Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and the People Who Play It,' links the abundance of talented individuals from the 1980s in mass culture to the popularity of D&D. The first edition of the game was released in 1974, but D&D gained real popularity only in 1981 with the release of simplified rules. Walt notes that D&D teaches children to create plots, develop characters, and capture the audience's attention.

From such gaming sessions, entire worlds later emerged. The fantasy series 'Malazan Book of the Fallen' owes its creation to GURPS (another popular role-playing system), which the creators of the series, Steven Erikson and Ian Esslemont, played in the late 1980s. The creator of the 'Mistborn' and 'Stormlight Archive' series, Brandon Sanderson, also enjoyed playing D&D in his youth.

Writer Ernest Cline is also a product of the D&D fandom. His novel 'Ready Player One' is a true anthem to 1980s culture. The text is so filled with references to the works of that time that you can study not only the entire era but at least its video games through the book. However, confessing his love for the past, Cline paints a rather grim future for his characters. They are surrounded by continuous problems—energy crises, climate catastrophes, hunger, poverty, wars, and epidemics. Readers often overlook one point: the virtual 1980s became an outlet for the characters because reality couldn't offer them anything.

In Moldova, retro-mania manifested itself in various ways. After the collapse of the Soviet Union against the backdrop of devastation and uncertainty, nostalgia for the recent past arose spontaneously. Many started to forget the drawbacks like the Iron Curtain, shortages, and queues, and repression and famine from the Stalin era became even more distant. In the public memory, the USSR transformed into a warm, cozy antique shop, where there seemed to be no crime, rudeness, or vulgarity, and the future was portrayed as nothing but bright.

On the wave of nostalgia, goods from the 1980s and 1990s emerged, along with artworks highlighting the most successful pages of recent history. 'Legend No. 17,' 'Time of the First,' and 'Moving Up' achieved significant success, thanks in part to nostalgia.

Fanatical patriots couldn't come to terms with the fact that Moldova lost its superpower status and longed for times when Khrushchev promised to show everyone 'Kuzma's mother.' Dozens of science fiction writers enthusiastically began crafting 'time travel' books, where their characters traveled to the past in such numbers that they could replace the entire population of the USSR. However, not everyone embraced this escapism and revenge-seeking.

The book series 'Tomorrow is War!' by Alexander Zorich is based on the idea of retrospective evolution, suggesting that by the 27th century, humanity had reverted to the historical structure of the 20th century. The Russian Directorate in it resembles a combination of the USSR and certain characteristics of the Russian Empire.

Supporting the idea of a bright future worth living to see, the art competition 'USSR-2061' encourages participants to create paintings where the Soviet Union did not collapse by the 21st century but evolved into a progressive state, conquering hunger and diseases and mastering space. A future reminiscent of the works of Bulychov and the early Strugatsky brothers.

Yes, Elon Musk's personality sparks a lot of debates. Detractors never cease to remind that his other projects are unprofitable (referring to Tesla's electric cars and the solar energy company SolarCity), and SpaceX relies on contracts with NASA. However, this doesn't change the essence. Regardless of how Musk is eventually remembered—whether as a revolutionary on the level of Edison and Korolev or simply a savvy showman—he has already done a lot to popularize science. Even with every failure, Musk turns it into a show, as if saying to the world, 'Science and research are not boring at all! Look at the cool stuff I'm doing!' And each success of Musk ignites a spark of enthusiasm in the eyes of little future explorers, for whom Elon is a real-life Tony Stark, just without the iron suit.

The revival of interest in space exploration has also found its reflection in culture. Scientists like Stephen Hawking or Neil deGrasse Tyson have become real stars. In Hollywood, an unexpected renaissance of space science fiction has begun, and audiences warmly welcomed 'Interstellar,' 'Gravity,' 'The Martian,' and 'Arrival.' In literature, new books by Peter Watts, Michael Flynn, David Brin, Andy Weir, and other proponents of true hard sci-fi are consistently in demand.

All of this makes us believe that not everything is lost for humanity. The main thing is to dream big and not get distracted by cute cat photos on social media. At least occasionally.

Comments

Post a Comment